Emancipation in Massachusetts

Inquiry Question: What tactics did enslaved people in Massachusetts in the 1700s use to free themselves?

- Background context for students

-

There is a common belief that slavery was less brutal or nonexistent in the North and that the North was a place where enslaved people could go to be free. However, in reality, Massachusetts and other northern states benefited from enslaved people’s work from the beginning. Boston Harbor was an important trading port for slave ships that would stop there before continuing to the South. And many of the important leaders in the North owned slaves themselves such as John Hancock.

Phillis Wheatley negotiated her freedom from her enslaver in 1773 Enslaved peoples in the North as well as the South resisted their enslavement in ways both big and small. Enslaved people regularly broke tools, stopped work or worked slowly, and they ran away as a way to prevent their enslavers

from benefiting from their labor. They also tried to build and keep families, maintain religious practices and languages, and educate themselves. They created communities and tried to remain connected to their African roots. In addition, enslaved people used the courts and legal avenues to become free. They wrote petitions to local and state governments, hired lawyers and fought for their freedom in court, bought their own freedom, and negotiated with their enslavers to manumit them–that is, free them without exchanging money.

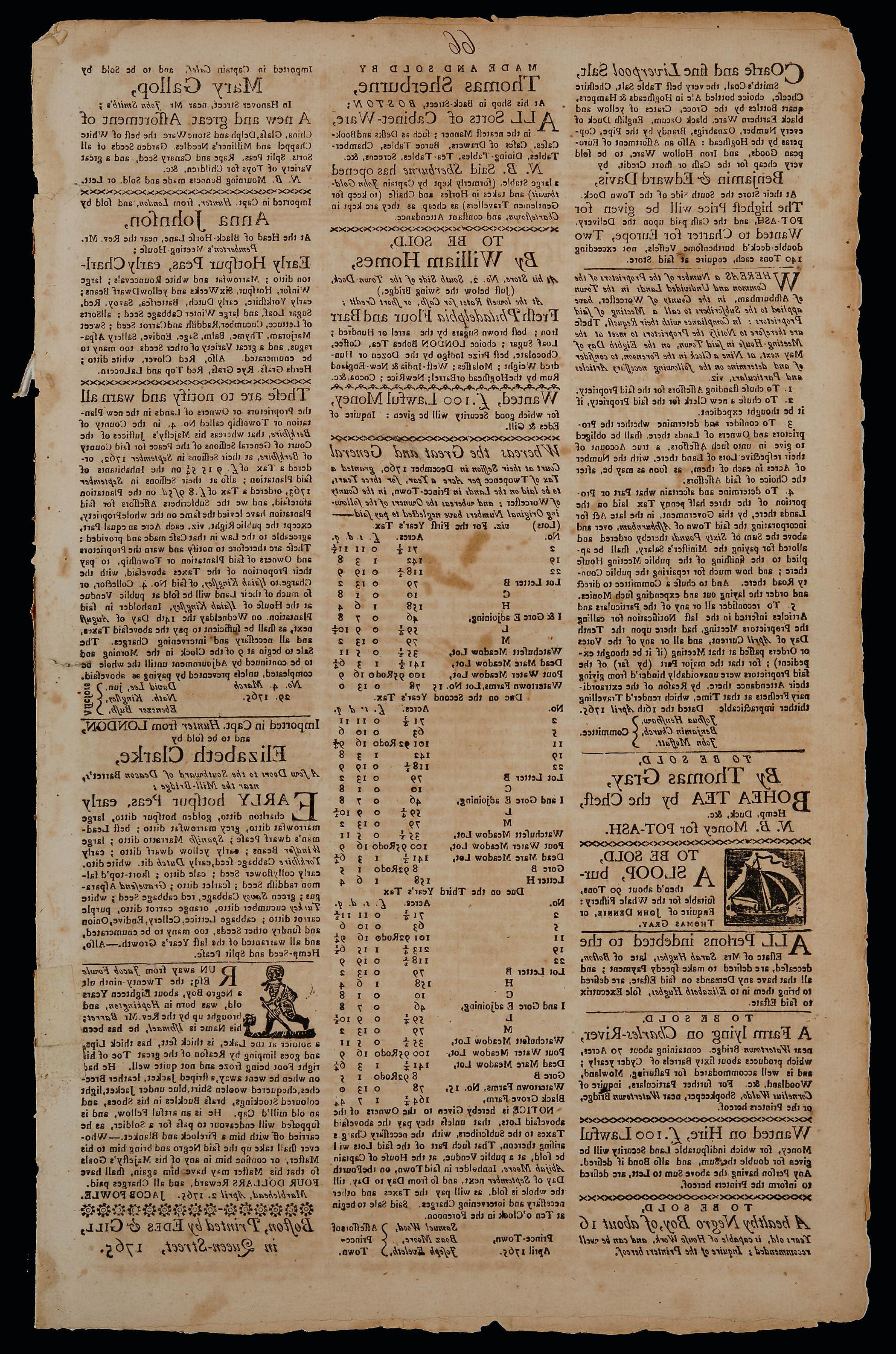

Boston newspapers featured ads for enslaved people who had run away Despite their efforts, white enslavers worked just as hard to keep control over those who had found ways out of enslavement. Northern cities like Boston created rules saying enslaved people could not be out late at night without written permission, and used patrols to enforce the rules.

Enslavers also placed “fugitive slave” ads in newspapers. These ads–written after an enslaved person had run away or fled from their enslaver–encouraged white people to find and return enslaved peoples to their enslavers. They were detailed and offered rewards for the capture and return of individuals who had escaped. These ads showed how valuable enslaved peoples were to white enslavers. Written by enslavers, the ads often describe runaways in racist, dehumanizing ways. However, as readers, we can try to read the ads from the perspective of the enslaved – what skills does the ad tell us they had? Does it suggest the reason why they ran away, or methods they took to protect themselves? Running away was dangerous and risky–if caught, the person could be harmed or sold far away. Each ad is a glimpse into one person’s brave bid for freedom, and the ways in which they tried to accomplish it.

Source Set

Download Source Set

Glossary

Enslaver (n.): a person who owned one or more other people; enslavers controlled the work and movement of the people they enslaved, and usually did not pay them for their work

Enslaved (adj.): An enslaved person is someone who is forced to work for another person for free for their whole lives; their time and movement is controlled by their enslaver.

Self-emancipation / self-liberation: the act of freeing oneself from slavery (e.g., an enslaved person who ran away from the place where they were enslaved self-liberated themselves)

Deposition: a written statement taken from someone; usually used in court / a legal case

Petition: a written request to an authority (e.g., Legislature), usually signed by many people

Advertisement: a public announcement

Analyzing Point of View and Voice

Who is the subject of the source?

- Who is the story about? Or, who is pictured?

Who is telling the story?

- What is their relationship to the subject?

Does the enslaved person speak for themselves?

Who is the audience?

- To whom is the story being told?

How credible is this source? Why?

Created by MHS staff and Katharine Cortes, PhD, University of California, Davis

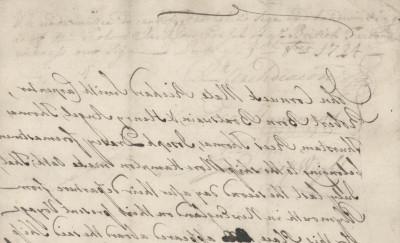

...the second day after their departure from Plymouth in New England on their present Voyage for [Portugal], appeared aboard the said Ship a Negro Man that calls himself Pompey, and he... had fled from a Shallop that appertained to the said Richard Trevit because of the bad usage he had received from him, & that about Twelve of the Clock in the night he Privately got aboard the ship while she lay at Anchor, by means of a Cannon that was then by the Shore Side.

In the fall of 1724, an enslaved man named Pompey self-liberated by boarding a ship docked in Plymouth, MA, in the middle of the night. The crew aboard the ship discovered Pompey once they were at sea. When the ship reached its destination of Porto, Portugal, the crew gave a deposition before the British consul, Robert Jackson, on 7 October 1724. In the deposition, they described how and why Pompey hid aboard their ship.

Citation: Deposition of John Cornuck and others regarding Pompey (a freedom seeker), 7 October 1724, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/629.

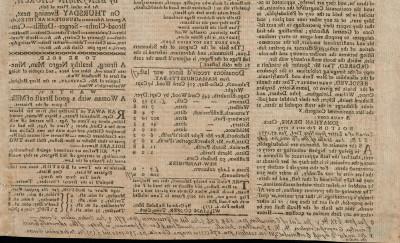

He is an artful Fellow, and is supposed will endeavor to pass for a Soldier, as he carried off with him a Firelock and Blanket.

On 2 April 1765, Jacob Fowle, a white enslaver, placed an advertisement in The Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal, a newspaper. Fowle was searching for 18-year-old Ishmael, who had run away from Fowle a few days earlier in an effort to free himself. Although he walked with a limp from a foot injury, Ishmael had experience as a soldier and Fowle thought he might try to pass himself off as a soldier again. Fowle offered $4 to anyone who found and returned Ishmael to him.

Citation: The Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal, 29 April 1765, Page 66, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/dorr/volume/1/sequence/76.

Read a transcript of the enslaver's advertisement searching to capture Dillar.

Ran - Away on Thursday last, from her Master Capt. Nathaniel Patten, a Negro Woman, named Dillar, about 30 Years of Age : She carried off with her a Child, about 5 Years of Age...

In 1775, a Black woman named Dillar ran away from Boston with her five-year-old child in an effort to free themselves. Their enslaver, Captain Nathaniel Patten, placed a newspaper advertisement asking others to help him find and re-enslave the pair.

Citation: The Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal, 6 February 1775 (includes supplement), Page 367, the Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/dorr/volume/4/sequence/749.

We expect great things from men who have made such a noble stand against the designs of their fellow-men to enslave them. We cannot but wish and hope Sir, that you will have the same grand object, we mean civil and religious liberty, in view in your next session. The divine spirit of freedom, seems to fire every humane breast on

this continent...

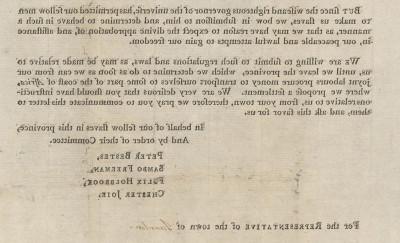

In 1773, Peter Bestes, Sambo Freeman, Felix Holbrook, and Chester Joie -- four enslaved men from Taunton, Massachusetts -- wrote a letter to representatives of the Massachusetts General Court (the Legislature), appealing for the freedom of themselves and all other enslaved people in the colony. With their freedom, they planned to establish a settlement on the coast of Africa. In the letter, which was published in newspapers, the men compare their desire for freedom with white colonists' growing revolutionary sentiments.

This was the first of seven petitions for abolition enslaved and free Black men sent the MA General Court in the 1770s. None of the petitions were successful, but all furthered the anti-slavery debate in MA and set an important precedent for collective action that later Black activists would continue to use.

Citation: Boston, April 20th, 1773. Sir, The efforts made by the legislative [sic] of this province ..., Boston, 1773, Circular letter signed "In behalf of our fellow slaves in this province, and by order of their committee ...", Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/443.

We have in common With all other men a natural right to our freedoms without Being depriv'd of them by our fellow men as we are a freeborn People and have never forfeited this Blessing any compact or agreement whatever...

In this document a group of enslaved people from Massachusetts petitions the colonial governor General Thomas Gage, the Council, and the Massachusetts House of Representatives, asserting that they share a common and natural right to be free with white citizens.

This was one of seven petitions for abolition enslaved and free Black men sent the MA General Court in the 1770s. None of the petitions were successful, but all but all furthered the anti-slavery debate in MA and set an important precedent for collective action that later Black activists would continue to use.

Citation: Petition for freedom to Massachusetts Governor Thomas Gage, His Majesty's Council, and the House of Representatives, 25 May 1774, From the Jeremy Belknap papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/549.

Read an excerpt where Wheatley Peters discusses her freedom.

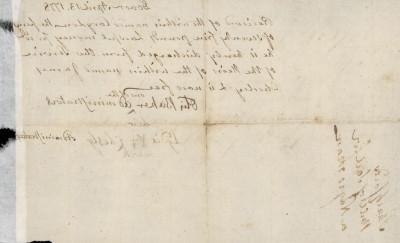

...the more subscribers there are, the more it will be for my advantage as I am to have half the sale of the Books, This I am the more solicitous for, as I am now upon my own footing and whatever I get by this is entirely mine, & it is the Chief I have to depend upon...

On October 18, 1773, Phillis Wheatley Peters wrote a letter to Colonel David Wooster of New Haven, C. On the second page of the letter she describes her new freedom and the importance of her book sales as a means of supporting herself.

Wheatley Peters had previously been enslaved in the home of Johnathan and Susannah Wheatley, a wealthy Boston family. She had traveled to London with the Wheatleys' son, Nathaniel, to promote her book of poems. Johnathan Wheatley manumitted Wheatley Peters before she returned to Boston. To manumit means to agree to free someone from slavery without exchanging any money. In her letter, Wheatley Peters describes sending a copy of her freedom papers to a London lawyer as a means of protecting her freedom.

(She later married a free Black man named John Peters, which is why we refer to her as "Phillis Wheatley Peters.")

Citation: Phillis Wheatley to David Wooster, 18 October 1774, Massachusetts Historical Society, euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/771.

Received [from] Corydon the sum of seventy five pounds Lawful money for which he is hereby discharged from the Service of … James Chesley & is now free.

In 1756, James Chesley paid 600 pounds to enslave a 16-year-old Black boy named Corydon. Chesley and his wife Lydia purchased Corydon from a white man named William Shackleford. In 1778, Corydon, then 38-years-old, paid 75 pounds to buy his freedom from his enslavers. The 1756 bill-of-sale and the 1778 freedom receipt are written on two sides of the same piece of paper.

Citation: Receipt from William Shackford to James Chesley for sale of Corradan (Corydon) (an enslaved person), 19 July 1756, Page 2 is a receipt of payment in exchange for freedom of Corydon signed by Otis Baker, "one of the administrators," 13 April 1778. From the Jeremy Belknap papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/545.

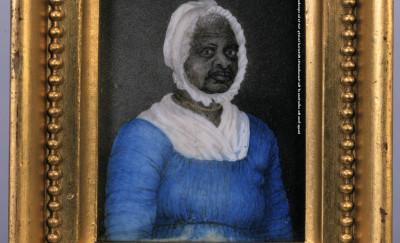

Any time, any time while I was a slave, if one minute's freedom had been offered to me & I had been told I must die at the end of that minute I would have taken it -- just to stand one minute on God's earth a free woman -- I would.

- Elizabeth Freeman, as quoted in a biography written by Catherine Maria Sedgwick, 1853

Elizabeth Freeman sued for her freedom from her enslaver, Colonel John Ashley of Sheffield, Massachusetts, in 1781. Her case set the legal precedent for the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. Her lawyer, Theodore Sedgwick, argued that Freeman should be freed under the Bill of Rights of the Massachusetts Constitution, which reads, "all men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential, and inalienable rights."

Freeman is often referred to as "Mumbet," used by the Sedgwick family and other white people when talking about her. We think it is important to call her by the name that she chose for herself as a free woman.

Citation: Elizabeth Freeman ("Mumbet") Miniature portrait, watercolor on ivory by Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick, 1811, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/23.

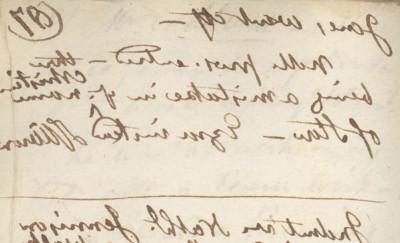

our Constitution of Government, by which the people of this Commonwealth have solemnly bound themselves, Sets out with declaring that all men are born free & equal – & that Every subject is entitled to Liberty, & to have it guarded by the Laws, as well as Life & property -- & in short is totally repugnant to the Idea of being born Slaves

In 1781, Quock Walker liberated himself from slavery when he ran away from his enslaver, Nathaniel Jennison, in Worcester County. Walker had been promised his freedom when he turned 25 and his enslaver did not honor that promise. Walker then sued Jennison.

William Cushing, the chief justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, kept these legal notes during the Walker v. Jennison trial. It includes notes on context, witness testimonies, and Cushing's interpretation of the case. When Judge Cushing gave the jury instructions, he told them that slavery could not exist under the new Constitution of Massachusetts. The jury found Walker to be a free man.

Citation: Legal notes by William Cushing about the Quock Walker case, [1783], From the William Cushing judicial notebook, Sequence of 13 pages presented--pages 87 [second page 87]-99., Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/630.

For Teachers

Emancipation in Massachusetts

Background Reading

- Additional context for teachers

-

Teacher Background

It is a serious misconception that slavery was less brutal or was even absent in the North. That slavery was a southern problem and the north offered sanctuary. In truth, slavery existed in the northern colonies. In fact, the Massachusetts Bay Colony created the first legal codification of chattel slavery in North America in its first legal code, "The Body of Liberties" in 1641. Boston Harbor was a major trading port for slave ships and merchants and Massachusetts residents alike benefited from the enslavement of Africans. While talk of “all men are created equal” and colonial desires to break free from the “shackles of slavery” spread throughout the colonies, men such as John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington kept captive men, women, and children dragged to the colonies from Africa.

Resistance to enslavement took many forms. Black men and women defied their captors in ways both big and small. Daily, enslaved people worked slowly, feigned illness, pretended incompetence, broke tools, and stopped work all with the goal of preventing their enslavers from benefiting from their unpaid labor. In addition, whenever possible they built and maintained kinship networks, religious practices, taught themselves to read and write, and preserved language networks that connected them to one another, and their African heritage. In addition, enslaved peoples also demanded their freedom by running away, purchasing their freedom and the freedom of their loved ones, negotiating for freedom by manumission, petitioning their local and state governments for freedom, and a few brought legal cases calling for their release from enslavement. Through these acts, enslaved peoples asserted their humanity and demanded agency over their lives.

One of the ways that white enslavers attempted to reclaim the people they enslaved was through “fugitive slave” ads. Ads were often highly detailed offering descriptions of individuals including their names and ages, any distinctive physical features including injuries inflicted by their enslavers, when they escaped, where they might be headed, their literacy abilities, and special skills. All with the goal of providing white individuals with ways to identify them. Rewards offered for some enslaved people enticed white individuals to capture and send individuals back to their enslavers. These ads also illuminate the value that white enslavers placed on those they held. Some ads offer large rewards and others describe in detail the high level of skill that some enslaved peoples had, both of which indicate how valuable they were as individuals while at the same time dehumanizing them. Enslavers wrote these ads, but through them we can also sometimes learn about an enslaved person’s motivations for and methods of running away, and the steps they took to successfully evade their enslaver and become free. Although we don’t know the ultimate outcome–did the person become free or were they caught?--each ad shows a person’s desire for freedom, and their brave attempt to secure it. This Google doc contains a sampling of runaway ads placed in Boston newspapers between 1765-1776. They all come from the MHS' digitized Harbottle Dorr newspaper collection.

White enslavers also established a system of patrols, jobs focused on catching “fugitives,” and state laws all designed to return “fugitive slaves” back to their enslavers. While slavery was legal in Massachusetts, towns like Boston had laws that stated no enslaved people could be out past 9:00pm without written permission or a lantern. These laws aimed to control and restrict the movement–and potential escape– of all enslaved people. Furthermore, the Fugitive Slave Law was established in 1793 and was used by white enslavers to demand the return of their captives and scare individuals from aiding people escaping enslavement. A fine of $500 and a year in prison for anyone caught aiding “fugitive slaves” made it all the more difficult for enslaved people to find solace. Although slavery in Massachusetts ended in the 1780s, Massachusetts courts and governments continued to uphold the Fugitive Slave Law, and, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Massachusetts’ free Black population was small.

Sources

- The Struggle for Freedom, African Americans and the End of Slavery in MA (MHS)

- Fugitive Slave Ads: Topics in Chronicling America (Library of Congress Research Guide)

- Teaching Hard History: Slavery and Resistance (Learning for Justice)

- Massachusetts Constitution and the Abolition of Slavery | Mass.gov

- Transcripts of Elizabeth Freeman's court records (ElizabethFreeman.mumbet.com)

- Elizabeth Freeman: A Free Woman | She Shapes History | Berkshire Museum

Inquiry Questions

- Questions for each document in the source set

-

Source: Pompey sailed to freedom, deposition, 1724

- According to the “More Hampton” ship’s crew, why did Pompey self-liberate?

- When and where did he board the “More Hampton”? Why do you think he chose this time and hiding spot?

Glossary:

- Shallop: a small, open boat used in shallow waters

- Appertained: belonged

- “Bad usage”: poor treatment

- Consul: a government official living in a foreign country whose job it is to represent the commercial interests of their own country

Source: Justice Cushing’s Legal Notes on the Quock Walker case, 1783

- What were the obstacles that Walker needed to overcome in order to successfully bring this suit against his enslaver?

- What are Cushing’s arguments about why slavery cannot continue?

Sources: Elizabeth Freeman's Sues for Freedom (excerpts)

- How did Freeman and her lawyers use the language in Article I of the MA Constitution’s Bill of Rights to argue against slavery?

- How does Freeman’s quotation – below her portrait – support the words in Article I?

- Compare Freeman’s portrait to the portrait of enslaver Samuel Shrimpton. The person he enslaved can be seen in the background (Zoom in).

- Freeman’s portrait was painted in 1811, after she had been free for 28 years. What story does each painting tell?

Source: Receipt for Corydon’s freedom, 1778

- What challenges were there for an enslaved person to purchase their freedom?

Sources: Freedom Petitions (1773 and 1774)

- What were the petitioners asking for in each petition?

- On what grounds do the petitions argue for freedom?

- How do the petitions–as a form–differ from the other tactics used to achieve freedom?

Source: Phillis Wheatley Peters’ manumission and letter to David Wooster, 1773 (p. 2)

- What is Phillis Wheatley’s purpose in writing to Wooster?

- How did freedom change her relationship to her book sales?

- Why might Wheatley have sent a copy of the contract stating the terms of her freedom to a London-based lawyer?

Source: Dillar, runaway slave ad, The Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal, 6 February 1775

- What do we know about Dillar’s enslaver?

- What does Dillar’s “homespun” tell us about one of her skills?

- Why do you think this ad was so short as compared to others?

- What obstacles might Dillar have encountered attempting to escape with a small child?

- What warning is given at the end of the ad, and to whom is it directed?

- What might this tell us about paths to freedom enslaved people took?

Glossary:

- Homespun: simple cloth or fabric made at home

- Cambleteen: a fabric consisting of a blend of wool, goat’s hair and cotton

- Harbouring: giving shelter or safety to

Source: Ishmael, runaway slave ad, The Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal, 29 April 1765

- What does it mean to have been a “Soldier at the Lake”?

- What do we know about Ishmael’s life so far, and the men who enslaved him?

- Why was it important to mention that Ishmael had a frozen big toe on his right foot?

- What do you think it means to be an “artful fellow”?

- Note: “artful” is usually used in a negative way. It means “clever at getting what you want, sometimes by not telling the truth.”

- How might being “artful” have helped Ishmael escape Fowle? What other words could be used in place of “artful” to describe the same characteristic, but in a positive way?

Suggested Activities

- Self-Emancipation (Runaway Slave) Newspaper Ad Analysis

-

Materials:

"Runaway slave" newspaper ad analysis worksheets and handouts

MA Self-Emancipation Newspaper Ads

- These ads span 1765-1776 and are a sampling of runaway slave ads that can be found in the pages of Massachusetts newspapers held by the MHS and digitized in the Harbottle Dorr collection.

Teacher Directions:

In this activity, students are asked to closely read and compare three “runaway slave” ads. They will then engage in a group discussion to answer inquiry questions.Divide students into groups of three and provide each group with the handouts - the 3 “fugitive slave” ads, the data collection charts, and the note-taking sheet.

- You can find all of the ads transcribed (alongside the original images) in this Google doc.

Read: Each student becomes an expert on one of the ads and then reads the other two ads for information.

Fill out the chart: Students complete the data collection charts and read over the other ad descriptions provided noticing patterns. Consider providing an annotation guide for students to use on the data collection sheet.

Discuss: Each group will use the inquiry questions provided to discuss the significance of the ads. Students should take notes with their ideas and any questions they have about the sources.

Inquiry questions for student discussion:

- What do you notice about how enslaved persons are described?

- What are some similarities and differences? (e.g., age, gender, physical attributes, skills)

- What do the differences between the descriptions tell you about the lives of the enslaved persons? About their white enslavers?

- Why do you think the ads are so detailed?

- Based on these ads, what did people escaping enslavement do to help improve their chances of success?

Layer in sources: After the initial discussion, introduce to the class the Boston “slave patrol” town notices of 1765 and 1766. These town laws were an attempt to control and limit the movement of enslaved people and indentured people of color, and to prevent them from freeing themselves. Read the two town notices as a class.

Discuss: Students then return to their groups of three to answer one final inquiry question: What role do you think these laws played for enslaved people trying to escape their captivity? - Wonder Walk: Methods of Self-Emancipation

-

Materials:

Wonder Walk worksheet with document excerpts

Teacher Directions:

This wonder walk allows students to explore the ways that enslaved persons emancipated themselves - legal cases, petitions, purchasing freedom, running and sailing away, and negotiating a manumission. This activity has students participate in a wonder walk where they will “Notice” and “Wonder” in groups. It can be used as an opening activity for a longer study on resistance to enslavement.

Create six (or eight depending on the number of students per group) stations around the room. Adhere one of the printables in the worksheet to each poster and write in a T-chart using “Notice” and “Wonder.” In groups, students move about the room adding their notices and wonderings about each of the primary source sets. Each group should have a unique color marker to track their comments around the room. After students have engaged with all four of the source sets, hold a full class discussion about the ways that enslaved people self-emancipated. Inquiry questions to guide the discussion include:-

What surprised you most about the ways people self-emancipated?

-

What obstacles do you think made self-emancipation difficult or impossible?

-

In what ways do you think the method of self-emancipation affected life after enslavement?

-

What do you think the response of white Americans was to the various forms of self-emancipation?

Encourage students to use the PRES strategy as they share their ideas:

- Point - main idea

- Reason - explain the main idea

- Example - identify a piece of evidence to back up reason

- Summary - restate main idea

-

- Analyzing Rhetoric: Freedom Petitions (9-12)

-

Materials:

Freedom Petitions, 1773-1777, Transcriptions

Freedom Petition Analysis Worksheet

Context:

Between 1773-1777, free and enslaved Black men filed seven petitions with the Massachusetts Legislature, calling for the emancipation of all people in Massachusetts. The petitions were also printed as broadsides and in newsletters, creating a lot of public debate around the question of slavery. Unlike other methods enslaved people used to free themselves on the individual level, petitions argued for the emancipation of all people across Massachusetts. Ultimately, all of the petitions failed. However, Black activists and white allies would continue--and still continue--to use petitions and the power of the printed word to advocate for equality and civil rights.The Massachusetts Historical Society holds four freedom petitions in its collections. Two of the petitions appear in this source set, and all four of the petitions are used in this activity.

Directions:

Introduction: Using the context above, introduce students to freedom petitions as a type of source. Explain that enslaved and free Black men petitioned the MA Legislature 7 times during the 1770s, and that they will be taking notes on four of them. Unlike other tactics used to achieve freedom, the petitions aimed to free all enslaved people in MA. The petitions did not end slavery in MA, but they created debate and a lasting tradition of Black activists using the power of the written word to push for change.

Read: Break students into 4 groups. Each group will be assigned one petition. Students should read the petitions independently and then take notes using the Analysis chart.

- In this activity, students are looking both at content (what request do petitioners make? On what grounds are they arguing for emancipation?) and rhetoric (How are they making their argument? What words do they use, and what emotions do those words convey?)

Report out: As a class, each group will report out on their petition. Go chronologically, beginning with Petition 1 and ending with Petition 4. Students should use the chart to take notes on the three petitions they did not read.

Discuss: Ask students, "How did the petitions change or remain the same over time?

Students should use specific evidence to answer this question. They can look at both requests petitioners made and also the ways in which the language changed or remained consistent across petitions.

Applicable Standards

- MA History and Social Science Frameworks

-

Skill Standards

Organize information and data from multiple primary and secondary sources

Analyze the purpose and point of view of each source; distinguish opinion from fact.

Content Standards

Grade 3, Topic 5, The Puritans, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Native Peoples, and Africans

Grade 5, Topic 1, Early Colonization and Growth of Colonies

Grade 8, Topic 4, Rights and Responsibilities of Citizens

USH1, Topic 1, Origins of the Revolution and Constitution

- C3 Frameworks

-

D2.His.16.3-5. Use evidence to develop a claim about the past.

D2.His.16.6-8. Organize applicable evidence into a coherent argument about the past.

D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

D2.His.8.9-12. Analyze how current interpretations of the past are limited by the extent to which available historical sources represent perspectives of people at the time

Additional Resources

Emancipation in Massachusetts

Additional Resources for teaching about resistance, emancipation, and civil rights in 18th century America

- Resources on: Fugitive Slave ads

-

This blog post discusses a 1771 runaway slave ad from a newspaper held by the MHS. The freedom seeker was an enslaved person known by two names: the masculine "Cato" and the feminine "Miss Betty Cooper." In the blog post, Caitlin G.D. Hopkins, PhD, discusses Cooper's gender expression in the context of the late 18th century.

The Annotated Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr (ngskmc-eis.net)

All of the runaway slave ads featured in this source set and suggested activities came from the Annotates Newspapers of Harbottle Dorr. This digitized collection is a complete four volume set of Revolutionary-era Boston newspapers and pamphlets collected, annotated, and indexed by Harbottle Dorr, Jr., a shopkeeper in Boston. The newspapers are a rich source for revolutionary thought and politics, and more broadly, life and customs in late 18th century Boston.

Freedom on the Move | Cornell University

Freedom on the Move is a database featuring thousands of transcribed runaway ads from newspapers across the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries. The K-12 educator page also has four lessons on using runaway ads in the classroom to teach students about resistance to slavery.

- Resources on: African American Petitions in the 18th century

-

The MHS holds four of the seven freedom petitions submitted to the MA royal governor and General Court (Legislature) in the 1770s. All four of these petitions, transcriptions of which are used in the "Analyzing Rhetoric: Freedom Petitions" activity in this source set, can be found on this webpage, which is part of the larger web feature "African Americans and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts."

Petition of Prince Hall to the Massachusetts General Court, 27 February 1788 (MHS)

Prince Hall and other free Black men of Boston presented this petition to the General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. It protests the unlawful seizure of three free Black men who were kidnapped in Boston Harbor and taken to the West Indies to be sold into slavery. Sailing was one of few occupations available to Black men at this time, and the petition states, in part, the weak laws protecting Black sailors. Two separate petitions on the same topic were submitted by a group of Quakers and the Boston clergy. One month after Hall's petition, on 26 March 1788, the MA legislature adopted an act to prohibit the slave trade.

Belinda Sutton and Her Petitions – The Royall House and Slave Quarters

Belinda Sutton was an African-born woman enslaved by the wealthy Royall family in Medford, MA. In 1783, Sutton petitioned the MA legislature for a pension for herself and her daughter from the proceeds of Isaac Royall's estate. She was granted an annual payment, but later submitted a second petition when she failed to receive all of the money the family owed her. The Royall House and Slave Quarters has a digitized copy of Sutton's first petition, plus additional contextual information about Sutton and her petitions.

- Resources on: Freedom Lawsuits

-

Massachusetts Constitution and the Abolition of Slavery | Mass.gov

The Massachusetts State Archives has additional primary and secondary source material on the lawsuits filed by Elizabeth Freeman and Quock Walker.

- Resources on: Phillis Wheatley Peters

-

A note on her name:

Kidnapped from west Africa around the time she was seven or eight years old, we do not know the name her parents' gave her at birth. Phillis--the first name her enslavers gave her--came from the slave ship that forcibly brought her to Boston. Wheatley--the surname by which she is most well-known--was the surname of her enslavers. As a free woman, she married a free Black man named John Peters. In a letter to her friend Obour Tanner following her marriage, she signed her name "Phillis Peters." The Education team at the MHS thus chooses to identify her as "Phillis Wheatley Peters" to encompass the surname with which she is most identified and the one she later chose to use as a free, married woman.

Massachusetts Historical Society | Phillis Wheatley (ngskmc-eis.net)

The MHS web feature "African Americans and the End of Slavery in Massachusetts" includes a page on Wheatley Peters with links to many primary source material held in our collections, including poems and letters she wrote, the frontispiece of her book of poetry, and the writing desk she is believed to have used as both an enslaved and free woman.

Of particular interest to students may by Wheatley Peters' letters to Obour Tanner, a Black woman in Newport, Rhode Island. The two corresponded over many years, and Tanner helped to sell Wheatley Peters' books to people in Newport.

To learn more about Wheatley Peters' letters, listen to the MHS podcast episode on about her. The podcast features the scholar Dr. Tara Bynum.

Secondary Sources

Legacy in Courage: Black Changemakers in Massachusetts Past, Present, and Future (Primary Source and Long Road to Justice)

Watch a documentary video, accompanied by complementary lesson plans, on Black Changemakers in Massachusetts across history and into the present.

"Meet Elizabeth Freeman" Performance - Museum of the American Revolution (amrevmuseum.org)

A 27-minute performance, "'Meet Elizabeth Freeman' stars Tiffany Bacon as Elizabeth Freeman and was written by Teresa Miller for the Museum of the American Revolution."