Women and Nonimportation

Inquiry Question: How did women protest the Townshend Acts and aid the patriot cause?

-

Historical Context

-

Student Background

In the 1760s, the British government needed to raise money in order to pay for their wars in Europe and the colonies. To do this, they made several laws that taxed the people in the colonies for items such as sugar, tea, paper, glass, paint, and lead. One of those laws was called the Townshend Act (1767). The colonists found these laws unfair and made a nonimportation agreement. This agreement or boycott meant the colonists would not buy any items imported (or brought to the colonies) from England. This was a difficult thing to agree on because most of the goods that the colonists wore, ate, and used, came from England. There was very little manufacturing done in the colonies. The boycott would last until the end of the war and would be difficult to maintain. Higher quality goods from England were so tempting to colonists and many would break the agreements, even those who were strong Patriots.

Women played important roles in making the boycott of goods from England successful. Wealthy white women pressured their families and their communities to only buy goods made in the Americas. White women of all backgrounds, but mainly young unmarried women, held spinning bees to make yarn from raw cotton, wool, and other fibers. The yarn they made was turned into clothes known as “homespun” because it was made in America. These spinning bees were public events where lots of people watched. The impressive amount that women produced during these events was recorded in the newspaper. They were important because at the time of the Revolution, women were not allowed to participate in politics. But these events allowed women to share their political opinions while still doing what was considered female work.

Wearing homespun clothes was a new experience for many wealthy and middle class white women, but it was not new to most people. Rural, working class, and enslaved people made their own fabrics long before the nonimportation boycotts. For example, Black enslaved women would work in the fields, process the cotton and indigo they picked, and then spin and weave the fibers into fabric. While homespun dresses were a sign of a Patriot woman’s commitment to the cause, for the majority of colonists and enslaved persons, it was simply how they had always created clothes.

Source Set

Download Source Set

Glossary

Import: to bring in items from another country to sell

Non-importation: to stop bringing in items from another country to sell

Merchant: someone who buys and sells items, usually involves trade with other countries

Boycott: to refuse to buy certain things

Linen: a type of cloth made from flax

Spinning: the process of turning natural fibers into thread or yarn for making clothes

Homespun: cloth or yarn made at home

Analyzing Primary Sources

As you explore the primary sources in this set, consider these questions:

Who created this source?

- What is the author's opinion of importation from Britain?

Who is the audience?

What is the message of this source?

What does this source tell us about the role of women during the Revolutionary period?

- Where did women have power to make change?

- Where did women lack power?

- Is this true for all women, or only some women? Why do you think so?

Who is included? Who is excluded?

- Whose perspectives are represented in this source? Whose are left out or silenced?

Created by MHS staff and Katharine Cortes, PhD, University of California, Davis

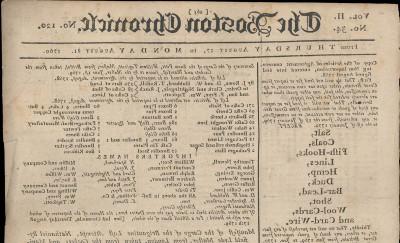

In August 1769, Boston newspaper publisher John Mein printed a list of ships, owners and merchants who ignored the non-importation agreement and continued to import and sell cargo from England.

Even John Hancock, a merchant and a member of the Sons of Liberty, continued to import goods from Great Britain, as can be seen in this newspaper.

Citation: The Boston Chronicle, Number 120, 17-21 August 1769, Boston: printed by Mein and Fleeming, 1769

Number 120 is also Volume II, Number 34, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/364.

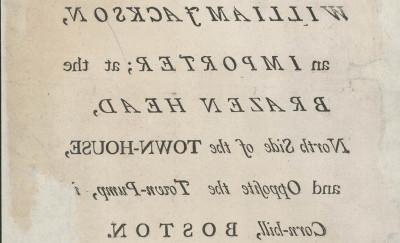

It is desired that the Sons and Daughters of LIBERTY, would not buy any one thing of him, for in so doing they will bring Disgrace upon themselves, and their Posterity, for ever and ever, AMEN

William Jackson was a Boston merchant who sold British goods at his store, the Brazen Head. In the winter of 1769-1770, patriots created this handbill and posted copies around Boston, urging townspeople to boycott his store.

Citation: William Jackson, an Importer; at the Brazen Head. Broadside [Boston, between 1768-1770], Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/365.

Read an excerpt of Adams' letter.

…for tho it was formerly the pride and ambition of Americans to indulge in the fashions and Manufactures of Great Brittain now she threatens us with her chains we will scorn to wear her livery, and shall think ourselves more decently attired in the coarse and plain vestures of our own Manufactury than in all the gaudy trapings that adorn the slave…

This portrait of Abigail Adams was painted by Benjamin Blyth around 1766, shortly after she married John Adams. In it, she wears a blue dress with a lace collar, three strands of pearls, and a ribbon tying back her hair. Many of the newspaper articles in this set mention “ribbons”; can you find where?

In 1774, Abigail Adams wrote a letter to Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay, a British historian, and described how women in Boston had stopped wearing fashionable clothes imported from Britain and instead begun wearing plain clothing made in the colonies. Part of Adams’ letter is quoted in the gray box.

Citation: Abigail Adams (Mrs. John Adams) Portrait, pastel on paper by Benjamin Blyth, circa 1766, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/69.

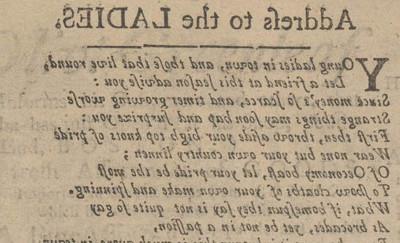

…What, if homespun they say is not quite so gay

As brocades, yet be not in a passion,

For when once it is known this is much wore in town,

One and all will cry out, 'tis the fashion !

And as one, all agree that you'll not married be

To such as will wear London Fact'ry :

But at first sight refuse, tell'em such you do chuse

As encourage our own Manufact'ry…

This poem was published in a Boston newspaper for women in November 1767, about nine months before Boston’s Nonimportation Agreement officially began. It encourages women to wear linen clothes and drink Labradore tea made in the colonies. The author also hints that young men will be attracted to such patriotic women.

Citation: Address to the Ladies, Verse from page 3 of The Boston Post-Boy & Advertiser, Number 535, 16 November 1767, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/380.

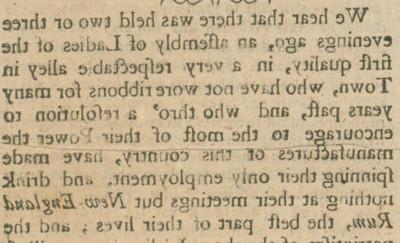

We hear that there was held… an assembly of Ladies of the first quality… who have not wore ribbons for many years past, and who thro' a resolution to encourage to the most of their Power the manufactures of this country, have made spinning their only employment, and drink nothing at their meetings but New England Rum, the best part of their lives…

In this newspaper article, the author discusses the important ways in which women can help the patriot cause. He focuses on locally made goods–that is, he talks about women who wear clothing they spin themselves, and who eat and drink items made in Massachusetts.

Citation: "We hear that there was held two or three evenings ago, an assembly of Ladies ..." Article from page 2 of The Massachusetts Gazette Extraordinary, Number 3351, 24 December 1767, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/294.

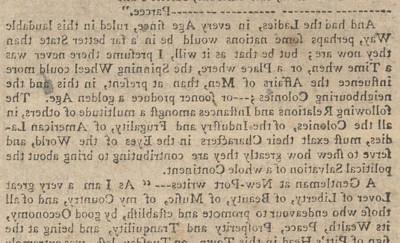

…I presume there never was a Time when, or a Place where, the Spinning Wheel could more influence the Affairs of Men, than at present, in this and the neighbouring Colonies…

This article, published in a Salem, Massachusetts, newspaper in May 1769, describes the ‘spinning matches’ women attended in Newport, Rhode Island and Long Island in New York, where they gathered together and made their own linen yarn so they could sew their own clothes. By making their own fabric and clothing, the women would be able to boycott British goods and help the patriots.

Citation: "March. 30. It was early conceived by the most sagacious and knowing Nations ..." Article from page 1 of The Essex Gazette, Volume 1, Number 44, 23-30 May 1769, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/390.

During the revolutionary era, William Dawes was a patriot who encouraged Bostonians to wear locally made clothing. He famously got married in a suit made in the colonies! Years later, his daughter Hannah Goldthwaite Newcomb ran a home shop system, paying several local women to spin and weave textiles for neighboring mills in Keene, New Hampshire.

This blue checked rectangle has the initials “LD” and was made for Newcomb’s sister.

Citation: Checkered cloth, Cotton, indigo dye by unknown maker, New England, late 18th or early 19th century, Massachusetts Historical Society, http://euro.ngskmc-eis.net/database/3545.

For Teachers

Historical Overviews for students and teachers

Excerpts of Newspaper Articles

Excerpt of Abigail Adams' letter

Created by MHS Staff and Katharine Cortes, PhD, University of California, Davis

Background Reading

-

Historical Overview: Women and Nonimportation

-

Teacher Background

The 18th Century was extraordinarily expensive for Great Britain. Several decades of war with France and Spain put a huge financial strain on the Crown and Parliament was eager to find ways to raise money quickly. After the Seven Years’ War, Great Britain passed a series of Acts and taxes aimed at gaining money from the colonies. The passage of the Sugar Act (1764), The Currency Act (1764), the Quartering Act (1765), and the Stamp Act (1765) all led to intense outcries from colonists who protested the lack of colonial representation in these decisions. By the end of 1765, organized protests through the colonies led to the passage of a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances.” While the protests, boycotts, and declarations eventually led to the repeal of the Stamp Act, Parliament continued to pass laws and tax colonial subjects.

In June of 1767, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts that specifically taxed tea, paper, glass, paint, and lead imported into the colonies. Named after Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was in charge of the Crown’s financial matters, this Act was passed to specifically replace lost income from Stamp Act boycotts. Given that the colonies had already demonstrated their ability to financially influence the Crown through boycotts, the goods named in this Act were intentionally chosen as ones that would be difficult for colonies to produce on their own. In response to the continued taxation without representation, colonists launched coordinated boycotts of goods coming from England. In 1774, a nonimportation agreement was signed at the first Continental Congress agreeing that the colonies would not import any goods from England. Traditionally, raw materials such as cotton, wool, silk, linen, and hemp were exported to England where they were made into finished goods shipped back to the Americas. These goods were generally cheaper and of better quality than those made in the colonies. However, the nonimportation boycotts shifted that balance and instead, those raw materials were turned into textiles and goods in America. This nonimportation agreement required the full and sustained participation of women in order to succeed.

Wealthy white women along with an emerging middling class consisting of former white indentured servants and wives of tradesmen played a key role in the nonimportation boycotts by promoting the homespun movement and creating a societal expectation to use only American produced goods. Spinning bees, where groups of white women from all backgrounds manufactured yarn for textile production, became public spectacles and were considered an acceptable way for women to express political opinions as it kept them within their traditional confines of household work. Women would spin and weave in public spaces and their accomplishments written up in newspapers for the evaluation and praise of their community. Colonists took pride in wearing homespun and being frugal became fashionable. Despite the widespread sense that women did not belong in politics, the homespun movement and the nonimportation boycotts brought women squarely inside political discussions.

It must be noted that while the homespun movement gave a significant amount of power to white women, wearing and using colonial made fabrics was not in fact novel. Rural and working class families had produced their own fabrics and materials long before the Revolution. For example, raising sheep, sheering their wool, and weaving the fibers for fabric was commonplace among colonists. In addition, while Black enslaved women were responsible for intense and often backbreaking work procuring the raw materials needed to support the spinning spectacles, they were also spinners and weavers themselves throughout the 1700s. An early textile industry was established through the forced and unpaid labor of enslaved women in the low country. They would work the fields, process cotton and indigo, and then spin and weave the fibers into fabric. While homespun dresses and adornments marked a Patriot woman’s commitment to the cause, for the majority of colonial individuals and enslaved persons, it was simply how they had always created their clothes.

Inquiry questions

- Document-specific inquiry questions

-

The Boston Chronicle, 21 August 1769

-

Why would the text of the agreement be printed in a newspaper?

-

Why do you think the names and contents of the ships violating the nonimportation agreements be printed in a newspaper?

-

What is the purpose of calling out violators of the agreement?

-

What affect do you think this had on individuals purchasing goods?

William Jackson, an Importer; at the Brazen Head, Boston, ca. 1768-1770

-

What is the role of an importer in a society?

-

How do nonimportation agreements change the role of a merchant?

-

What purpose was there in printing this call out of William Jackson?

-

This image was painted in 1766, in the middle of several nonimportation agreements, which of the items she is wearing would likely be part of the boycott?

-

In what ways do you think her clothing would change if this was painted in 1768 after the nonimportation agreements had been in place for a few years?

Letter from Abigail Adams to Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay, 1774

- Why does Adams use the language of enslavement so often?

- What is her purpose using it if white patriots are not actually enslaved by Great Britain?

- How might free and enslaved Black people have felt hearing the comparison?

“Address to the Ladies,” The Boston Post-Boy & Advertiser, 16 November 1767

- What is the purpose of posting this in the newspaper?

An assembly of Ladies, The Massachusetts Gazette Extraordinary, 24 December 1767

-

What is the purpose of posting this in the newspaper?

-

What kind of influence do you think it had over readers?

-

What product substitutions does it suggest?

-

What kind of influence do you think it had over readers?

Women’s Spinning Matches, Essex Gazette, May 1769

-

What is the purpose of posting this in the newspaper?

-

What kind of influence do you think it had over readers?

-

What product substitutions does it suggest?

-

Suggested Activities

Access all of the instructions and worksheets for the set's activities.

- Shipping Manifest Inquiry (Grades 3-5)

-

Teacher Directions 3-5

Materials: Shipping Manifest Worksheet and Transcription

This inquiry gives students the opportunity to engage with a primary document in its original form and yet, in a low stakes way. Before starting this activity, the teacher should give students background on what non-importation means

Background on Nonimportation and Discussion

Teacher projects the nonimportation agreement on the board, either its original form or a transcription. Students read the first and second paragraphs out loud for the class.

-

This is a good time to offer any background information on the agreement and why the items listed might be excluded from the boycott. Generally those items were allowed because there were no substitutes available in the colonies.

Have students google where the technology they use in the classroom (laptops, iPads, etc) is made or common foods they eat are grown. Then ask students: If the United States decided to boycott items from that country, do you think it would be easy or difficult for you to do without those items?

Analysis of Shipping Manifest

Before looking at the document, have a whole class discussion asking the question “What does it mean to be part of a boycott?” Allow students time to think about how boycotting items would affect day to day life. Consider introducing this activity by reading the book Pies from Nowhere: How Georgia Gilmore Sustained the Montgomery Bus Boycott by Dee Romito that talks about the daily struggles of a boycott. Students can draw connections between the role of women in the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the nonimportation boycotts. After the discussion, the teacher passes out the handout with a portion of the manifest from the Snow Pitts. Students circle items of clothing and box household items. In groups, students then brainstorm their answers to the two inquiry questions:

-

What do you think people did if they could not use boycotted items?

-

Why do you think it was a big deal that people continued to import goods on the boycott list?

Other discussion question suggestions:

-

Why was this agreement posted in the newspaper? Who was supposed to see it?

-

What is the purpose of a boycott?

-

- Close Reading Jigsaw

-

Jigsaw: Analyzing multiple primary source documents

Teacher Directions

Materials: Quote Analysis Charts -- there are two levels of the chart

In this activity, students will analyze three sets of quotes that highlight which goods were desirable for women to wear/use, and which ones were seen as unpatriotic.

Placing students in groups of 3, the teacher should provide each student with a copy of the primary source graphic organizer. Students will then jigsaw the quotes each becoming an expert on one. As they fill out the chart, they should look for patterns in the sources to see what type of substitutions the news articles recommend patriotic women use.

- Summarizing Main Idea: Writing Headlines

-

There are four newspaper articles in this source set and not one has an interesting title! Have students write their own headlines for the newspaper articles.

-

Divide students into groups. In this activity, each group will write a headline for one of the four newspaper articles in the source set.

-

Tell students: After a reporter writes a newspaper article, their editor writes a headline for it. The headline gives readers an idea of what the article is about–and tries to grab their attention so that they want to read it.

-

-

Assign each group of the newspaper articles that summarizes the article and captures a key aspect they feel is significant and important.

-

What is the main idea of this article?

-

Who is the audience for this article?

-

How does the author want the reader to feel about this topic?

-

What does the author want their readers to do after they read the article?

-

How can the headline help to persuade the reader to do what the author wants?

-

-

After students have discussed ideas and written a headline in their groups, allow them to stop and reflect.

-

Take a gallery walk to observe what headlines other groups wrote.

-

- Image Comparison

-

Materials: Image Comparison Worksheets (Novice and Advanced)

IQ: What were the two purposes of the homespun movement?

This activity asks students to evaluate two paintings and connect them to the larger homespun movement. The two images demonstrate that there were two distinct purposes of the homespun movement - socially acceptable political participation for women and necessary manufacturing of fabrics. The analysis of the two paintings should lead to fruitful conversations as a whole class about the purpose of the homespun spectacles and spinning bees.

The activity includes a “novice” worksheet and an “advanced” worksheet. For novice students, it is an ideal activity as a bell ringer as it is quick and engaging. For advanced students it might be helpful to review some of the elements of art analysis prior to the activity. Art analysis resources include: The Art of Seeing Art™ | The Toledo Museum of Art and Practice Looking at Art | The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (mfah.org).

-

Give each student a copy of either the ‘novice’ or ‘advanced’ handout.

-

On their own or in pairs, students study the two pictures and use the question prompts to aid their investigation.

-

As a whole class, guide students to notice some of the important details and make critical connections. Some possible questions to ask:

-

Who are the women in the images? What socio-economic class do you think they belong to?

-

What are the women in the images doing? Would they be doing that task if it wasn't part of the nonimportation boycott?

-

What is the difference in the purpose of the tasks shown in the two images? What do you think the people who had been making their own fabric prior to the nonimportation agreements thought about the homespun movement?

-

Who else do you think did similar work to the women in these images? Why do you think the artist left them out?

-

What do you think the artists' purposes were in painting these images after the American Revolution? What was their goal?

-

-

- Examining Rhetoric: Slavery and the American Revolution (Grades 9-12)

-

Examining Rhetoric: Slavery and the American Revolution

Teacher Directions (9-12)

Materials: Examining Rhetoric Worksheet

The rhetoric of white patriots of the American Revolution drew direct correlations to the enslavement of Africans and their descendants. This language analysis is a first step at helping students compare the language of the American Revolution, the Abolition movement, the philosophy of natural rights, and the American Constitution.

-

Place students into groups or allow them to complete the charts on their own.

-

Students first read excerpts from a letter Abigail Adams wrote that makes several direct references to white patriots being enslaved by Great Britain. They should be encouraged to mark up the text as they read. Students will then complete a “Means” and “Matters” section to analyze the excerpts.

-

Students will then move on to analyzing excerpts from three different pieces of writing from poet Phillis Wheatley. They complete the same “Means” and “Matters” section using different questions to guide their thinking.

-

The final assessment asks students to choose a method of communicating their thoughts - short essay, poem, song lyrics, draw a picture, etc to answer the question - How might a free or enslaved Black person feel hearing white Patriots say they are enslaved to Great Britain?

-

Applicable Standards

-

C3 Framework for Social Studies Standards

-

D2.Eco.2.3-5. Identify positive and negative incentives that influence the decisions people make

D2.His.4.3-5. Explain why individuals and groups during the same historical period differed in their perspectives.

D2.Eco.1.9-12. Analyze how incentives influence choices that may result in policies with a range of costs and benefits for different groups.

D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

-

MA 2018 HSS Standards

-

Practice Standards

Develop focused questions, or problem statements, and conduct inquiries.

Argue or explain conclusions, using valid reasoning and evidence.

Content Standards

Grade 3, Massachusetts in the 18th century through the American Revolution

g. the roles of colonial women in keeping households and farms, providing education for children, and, during the Revolution, boycotting English goods

Grade 5, Topic 2, Reasons for revolution, the Revolutionary War, and the formation of government

d. the role of women in the boycott of British textiles and tea, in writing to support liberty, in managing family farms and businesses, raising funds for the war, and supporting the Continental Army (1760s–1780s)

USH I. Topic 1, Origins of the Revolution and Constitution

Additional Resources

Women and Nonimportation

Additional Primary Sources at the MHS

In addition to primary sources on the role of women in nonimportation, the MHS has digitized primary sources that provide the opposing viewpoints of the Sons of Liberty and some of Boston’s merchants.

- Additional MHS Primary Sources on Nonimportation

-

MHS Collections Online: Extract of a Letter from London, dated July 27, 1770. (ngskmc-eis.net)

- MHS Web Feature

-

Coming of the American Revolution: Non-consumption and Non-importation (ngskmc-eis.net)

Digital Resources at External Institutions

The Elizabeth Murray Project (csulb.edu) (California State University, Long Beach)

Not all merchants in colonial Boston were men. Like William Jackson and John Hancock, Elizabeth Murray also imported and sold British goods. This website has primary sources related to Murray, colonial advertising, and colonial Boston; related secondary sources, and teaching resources and activities.

Edenton Tea Party - North Carolina History Project

In 1774, women in North Carolina formed the Edenton Tea Party in response to the 1773 Tea Act. To protest the Act, they resolved to boycott British cloth and tea. The women were ridiculed and satirized in Britain, but received a lot of support in the colonies. This webpage contains two primary source images and additional information about the Edenton Tea Party.

Colonial Women Spin for Liberty · SHEC: Resources for Teachers (cuny.edu) (SHEC: Resources for Teachers)

View a 1794 woodcut to see what a spinning loom looked like

"Catharine Macaulay: England's First Female Whig Historian, 1773-1774," by Bob Ruppert (Journal of the American Revolution)

Learn more about Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay and her correspondence with both Abigail and John Adams in the years leading up to the Revolutionary War.