By Meg Szydlik, Visitor Services Coordinator

Trigger warning: use of outdated but period-typical language to describe disabled individuals.

The third and (for now) final installment of my series on Disability in the Archive is a hopeful one. Read Part 1 and Part 2. As I investigated the treatment of disabled veterans, I had my first opportunity to use the actual voices of disabled people in this blog post. I examined the letters and photographs of Samuel “Sammy” Barres, a WWII bilateral amputee who wrote faithfully to his “sweetheart” Bernice and his mother, giving us a window into his thoughts. I am not a veteran and being deaf/hard of hearing is a very different disability, but in his letters, I see echoes of my own experiences.

The first things I noticed were how other people talk about him and his consistently overly positive attitude in response. After Sammy’s legs are amputated, one above the knee and one below, he receives letters from friends, all of whom clearly love him but who talk like his life is over and praise his cheerfulness. His friend Bill says, “reading the letter again, I began to notice your high morale and as I read more I couldn’t figure out how anyone under your circumstances could display such high spirits.” Sammy himself even says “how thankful I am for being spared my sight, and my hands, and my brain. Handicapped? Sure I am. But so very little, comparatively speaking.”

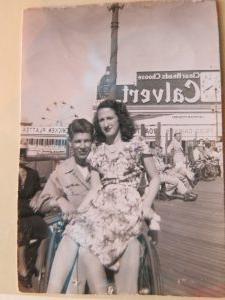

It is reminiscent of modern-day inspiration porn, which is when people create content around disabled people doing things that are only inspiring because they are disabled. For an excellent introduction, read this article and this article. In a more direct example, Sammy’s picture is shared to raise funds for amputees, which is one reason that inspiration porn gets made. Abled people feel grateful that they are not disabled and are more willing to participate. Inspiration porn asks: how can someone who is disabled continue to exist and even succeed? That is certainly a question I have been asked- directly and indirectly.

The differences between his letters to his mother and to Bernice are striking, and not just because he is lovesick for Bernice. Letters that were mailed around the same time and talk about the same things are far less cheerful and inspiring when he writes to his nurse “sweetheart” than when he writes to his mother. I have done similar things, kept the full truth from someone, either because they would overreact (as Sammy’s mother does), because I don’t want to be pitied, or even because I don’t want to explain all the background. Sometimes “fine” is the best answer! I’m sure that Sammy felt similarly. In fact, years later Bernice writes that “almost everything he wrote her [his mother] was the opposite of what he was experiencing.”

Another thing I noticed while reading is the extraordinary frustration of bureaucracy that was present then and is still present now. Sammy talks about how difficult it is to get help from the limb shop. He tells Bernice that he “went to the limb shop this morning to remind them that [he] was still alive” and then the very next day he “spent a very upsetting afternoon in the limb shop. And [he] still got nowhere.” That frustration is so common for chronically ill or disabled people. While in Boston his leg has a significant issue, and he struggles to find a place that can fix it for him. Similar things have certainly happened to me where getting my assistive device fixed was much more challenging than others think. Like Sammy, I am very good at troubleshooting and finding ways around things that break or around the limits my body has placed on me.

Hearing a disabled person’s own perspective was valuable. While Sammy Barres is only one man and his experience is not universal, it is a story worth telling as part of understanding disability and the presence of disability in the archives. In his case, he and Bernice married— over the objections of her family, who never spoke to Bernice again because she married her “legless love—” and had five children. They generally seem to have lived a happy and loving life, one where they were not separated long enough to write the stacks of letters telling their story, like they did during their engagement. This story has a happy ending! Not an easy one, but a happy one nonetheless.