By Hannah Goeselt, Library Assistant

“My grandfather’s clock was too tall for its shelf, so it spent 90 years on the floor…” Did you sing this nursery rhyme as a child? Written in 1876 by American composer Henry Clay Work (1832-1884), the oddly morbid song told from the perspective of a child observing the tall-case clock owned by his grandfather, is why this style of timepiece today is commonly referred to as a ‘grandfather clock’. In the period they were in fashion, however, they were termed ‘eight-day clocks,’ referring to how many days it ran before you had to wind it again.

Now, if you’ve ever visited the MHS for more than an hour, you may know that it is home to a wide assortment of old clocks, which you can hear chime throughout the day. Each week many are wound by a staff member with their own specialized keys and cranks. In this sense they are both a functional aspect of the building, and a part of the MHS’s collection, with their own individual records in Abigail.

The tall-case clock in the reading room, cataloged as ‘clocks 007’ is a beautiful example of New England clock design in the early republic, or the “Federal Period.” Southeastern Massachusetts, aka the South Shore, specifically between the years of 1790-1830 became a major center of weight-driven clock movement production in the region. This clock is and was a luxury household item, with its size and use of mahogany wood, the cost of the entire thing would be upwards of 60 dollars, more than a year’s worth of pay for the average American at the time. The trendiness of the grandfather clock was relatively short-lived, its cost being one major factor in its downfall. By 1825, regional manufacturers were struggling to compete with the new availability of Connecticut-made shelf clocks on the market, made with wooden movements rather than brass, and at a fraction of the cost. In fact, even by 1812 the grandfather clock was waning in popularity, in favor of patented banjo clocks and other smaller scale timepieces.

When I sit at the circulation desk, I occasionally feel my eyes slide toward its stately figure in the far corner and listen to the subtle clunk of internal gears several minutes before it prepares itself to ring.

The man responsible for these internal workings, “Old Quaker” Joshua Wilder (1786-1860), was a successful clockmaker in Hingham, Mass. and is today best known for his skill in crafting ‘dwarf clocks’, a scaled-down version of the grandfather clock (an example shown here from Historic New England collections). This was a style pretty much exclusively produced in Hingham and Hanover during the first quarter of the 19th century and was the solution to competing with the banjo clock patented and produced by the Willard family-owned workshops in Boston (the MHS also has an example of a Willard banjo clock, see ‘clock 006’). Within that circle, Wilder stood as one of the most prolific producers of dwarf clocks, though he still continued making movements for tall-case versions to a smaller extent.

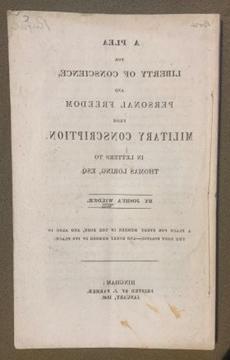

Wilder began his career as an apprentice to another prominent manufacturer, John Bailey II, in Hanover, MA and moved to Hingham around 1809-1810 to set up his own shop. We can see that that is where this piece originates- beneath the ornate brass hands the words “Joshua Wilder / HINGHAM” are painted in flowing script across the white dial. Quakers made up a disproportionate number of the clockmaker community, taking on as apprentices the sons of other Quakers and so on. Because of that, I was not surprised to learn that Wilder was involved in Hingham’s Temperance Society and Peace Society. I was, however, pleased to find out that the MHs owns one other piece by Wilder, showcasing his literary skills in addition to his skill in clockwork. The bound pamphlet, printed in Hingham in 1840, is a series of published letters to local Representative Thomas Loring (1789-1863) sharing Wilder’s opinions on forced conscription into military service. It reads more like a religious tract, each letter attempting to reconcile the observance of those who take a vow of non-violence with a duty to the law (both governmental and religious) to take up arms. In essence, he was advocating for a paid, as-needed Volunteer Service. While perhaps not the most exciting piece of writing, I did think it was interesting to have the inner thoughts behind an artifact’s manufacturer, a category of creator that can so easily be relegated to “anonymous” or “once known.”

Stay tuned for part 2!

BIB:

Jobe, Brock, Gary R. Sullivan, and Jack O’Brien. Harbor & Home: Furniture of Southeastern Massachusetts, 1710-1850, University Press of New England, 2009. (Oversize NK2435.M34 J55 2009)

Jobe, Brock. “A Tale of Two Clocks.” Historic New England (Summer 2011): 24-26. http://issuu.com/historicnewengland/docs/historic_new_england_summer_2011

Keane, Maribeth, and Brad Quinn. “Call Them Grandfather or Tall-Case, Gary Sullivan Knows Big Clocks.” Collectors Weekly, February 26, 2010. http://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/an-interview-with-tall-case-antique-clock-collector-gary-sullivan/